Law and Honor: The Legal Foundations of American Indian Treaties

In this article I briefly explain the basis of federal Indian law as drawn from the treaties entered into by the United States with Indian tribes.

Upon adoption of the United States Constitution, the very first treaty that the newly established Republic would sign was with an Indian tribe, that tribe being called the Delware1. Having acquired most of America’s land mass through nearly four hundred treaties that were negotiated with Indian tribes between 1787-1871, the terms of these treaties imply that the U.S federal government owes America’s precolonial populations the promises agreed upon within them2. The treaties from this era established the legal doctrine of “Trust Responsibility”-the principle that the U.S is supposed to fulfill the treaty obligations that they promised to honor in exchange for the land ceded to them by the American Indian3. Having established this trust relationship via treaties, the relationship in turn carries with it the expectation that the federal government works to support tribal self-government, self-determination, and economic prosperity4. However, extensive research into American Indian history reveals that federal policy regarding Indian tribes has not been static over the course of time. In turn, under careful investigation of why radical shifts in federal Indian policy have occurred it is apparent that policy changes have coincided with the cyclical transfers of power within the U.S government and with the varying political contexts from which policy changes were made—culminating in an inconsistent approach to managing federal Indian policy throughout history.

Considering that there are competing definitions of the term Indian between federal, state, and tribal governments in addition to the debate over the use of the term between Indians themselves-there is no universally agreed upon definition for who is considered an Indian5. Likewise, there is also no universal definition of what constitutes an Indian tribe6. Despite the debate over who is or who is not considered an Indian, there is one aspect of American policy which has become abundantly clear: Indian tribes are to be subordinate to the laws of the U.S federal government. After gaining independence from Great Britain, the U.S Supreme Court decided that Indians no longer had the right to property, and it was thus deemed acceptable for land to be taken from them and given to “Christian people”7. The origin of this legal position came from the case Johnson v. McIntosh in 1823, in which the court explained that the U.S government had gained ownership of all land possessed by Indians because Europeans had allegedly “discovered” the American continent and successfully “conquered” the tribal inhabitants8. The rationale of Johnson v. McIntosh, known as the “Doctrine of Discovery” became the basis for codifying the dispossession of Indian land and led to the creation of the American legal principle known as Indian title9. While Indian title maintains the position that the federal government can decide to take land away from Indian tribes at any time, the court in Johnson v. McIntosh determined that Indians still have a right to occupy and use their ancestral lands until the federal government decides otherwise-providing Indians a right of possession but not right of ownership over their ancestral homes10. The term Indian Country refers to all lands within an Indian reservation and all land outside an Indian reservation that have been designated primarily for Indian use under federal superintendence11.

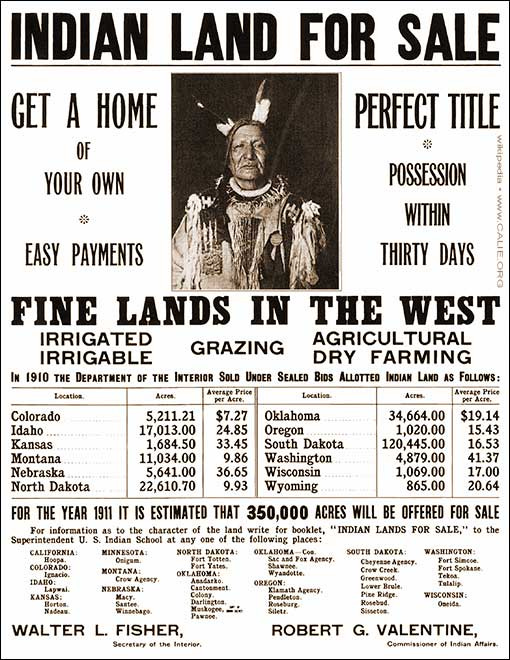

Today, forty percent of Indians live on or near Indian reservations12. There are approximately 315 reservations in the U.S, accounting for 2 percent of the country’s land mass13. As a group, tribal nations are the most disadvantaged in American society. Along with having a significantly lower life expectancy than typical Americans, unemployment rates on some reservations reach 80 percent; nearly a quarter of all Indians live in poverty, 14 percent of all reservations homes lack electricity, and 12 percent of all homes lack access to a safe water supply14. Moreover, the American Indian falls below national averages in education—half the adult population does not possess a high school diploma with only 14 percent possessing a college degree in comparison to 24 percent for the country as a whole15. While there are multiple contributors to the social conditions existing behind these figures, they are also in part the legacy of the 1887 General Allotment Act, also known as the Dawes Act, which reflected a view that the U.S government should break America’s promise to honor Indian tribal sovereignty and destroy the very basis of it by forced assimilation16. The Dawes Act divided communally held land into allotments which Indians would not be able to successfully farm due to their impoverished condition at the time and because of the unsuitable land which they were allocated-leading to many of them getting forced into selling their land parcels to Euro-American settlers as they were also unable to pay new state-imposed taxes17. The extent of this policy disaster is demonstrated by the fact that the amount of Indian held land was reduced from 138 million acres in 1887 to 48 million acres in 193418.

In contrast to the Dawes Act, the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) marked a shift away from undermining tribal sovereignty and instead focused on efforts to reverse some of the damage done during the allotment era. This landmark legislation came at the urging of former Commissioner of Indian Affairs and Franklen D. Roosevelt appointee John Collier, a prominent American critic of U.S Indian policy who at the time of the IRA’s passage said “No interference with Indian religious life or expression will hereafter be tolerated. The cultural history of Indians is in all respects to be considered equal to that of any non-Indian group”19. The expressed purpose of the IRA was to “rehabilitate the Indian’s economic life and give him a chance to develop the initiative destroyed by a century of oppression and paternalism”20. Among the reforms which the IRA advanced was the prohibition of further allotment on tribal land, allowing for the Secretary of the Interior to add lands to existing reservations, allowing for the creation of new reservations for tribes who lost their land, and the encouragement of tribes to create constitutions organized in a way similar to federally chartered corporations so that they could exercise self-government21. Furthermore, part of the IRA’s legacy has been increasing the amount of Indian held land by two million acres with additional investment into developing reservation health facilities, irrigation works, housing, schools, and roads22.

As illustrated by the differences in policy perspectives and approaches embodied in legislation like the Dawes Act and Indian Reorganization Act-transfers of power and changes in political contexts over the course of the 47 years of time separating the two pieces of legislation clearly show shifts in how federal Indian policy has been understood by U.S policy makers tasked with upholding America’s treaty obligations. Courts are vital in formulating the doctrine of Trust Responsibility due to the role that they play in interpreting the duties of the U.S in regard to their trust relationship with Indian people. In Rice v. Cayetano, the Supreme Court clarified that federal statutes passed by Congress can be used as a means to satisfy treaty obligations-making said statutes extensions of Indian treaties23. There are limits, however, to the power which the Court has to enforce treaty obligations on the behalf of tribes24. While a tribe can seek judicial relief for breaches in trust responsibilities by federal agencies, the Court lacks the power to force Congress to honor those responsibilities25.

Despite the judicial limitations for ensuring treaty compliance by Congress, the Court does hold the position that federal agencies managing tribal programs and resources have a fiduciary duty to do so in manner consistent with tribal interests and congressional intent26. The fiduciary duty of federal agencies was solidified in United States v. Mitchell I and United States v. Mitchell II27. Becoming known as a legal principle called the “Mitchell Doctrine” in 1983, the Supreme Court determined that the Quinault tribe was owed damages by the federal government due to violations of fiduciary duty owed to them by the Department of the Interior-setting a lasting legal precedent for future cases28. When regulating their territory, tribes may interpret the legal decision Montana v. United States to mean that they are permitted authority over non-Indians only within the context of preserving self-government and internal relations unless Congress explicitly gives them that authority otherwise29. The rationale of the courts in Montana was that giving Indian tribes jurisdiction over non-members over issues not directly related to tribal interests is beyond the parameters of preserving self-governance and is inconsistent with their dependency status with the federal government30. Reasoning from the precedent set in Montana, in the case Brendale v. Confederated Tribes and Bands of Yakima Indian Nation, the Supreme Court further clarified the parameters of tribal authority to zone lands within their reservations31. While noting that federal preemption barred state governmental organizations like Yakima County from assuming regulatory authority over tribal lands, the Court determined that tribes retain authority over the land use of non-Indians to the extent which they threaten their political, economic, and health related interests32. In the absence of such threats to tribal interests by non-Indians, land use regulation reverts to local non-Indian governments33.

In the ongoing effort to bring American policy into compliance with its treaty obligations to Indian people, litigation from the past might suggest that the complexities of accomplishing this task will continue to pose challenges for everyone involved in that process. Considering that the U.S has broken nearly all of the county’s treaties with Indians historically, one may argue that there is a significant amount of progress that remains to be made towards getting Americans to understand these obligations as legitimate and therefore worthy of protection34. For example, last year State Senator Keith Regier in Montana was trying to promote legislation seeking to abolish Indian Reservations—effectively eliminating tribal polities and taking away the last remnants of sovereignty that they have left35. This expressed contempt for Indian tribes is also reflected on the national level as former President Donald Trump never attended one meeting at the annual Tribal Nations summit during his term36. Taking lessons from history into account, however, if future dealings between tribes and the U.S can be conducted in better faith than in years prior there could be a chance for a relationship based on mutual terms: nation to nation, government to government.

A link to Senator Reiger’s draft resolution can be found here: https://leg.mt.gov/bills/2023/billpdf/LC1964.pdf

Notes:

Stephen F. Pevar, The Rights of Indians and Tribes (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), Kindle, p. 45.

Pevar, p. 29-30.

Pevar, p. 29-31.

Pevar, p. 32.

Pevar, p. 17.

Pevar, p. 18-19.

Pevar, p. 22-24.

Pevar, p. 22-24.

Pevar, p. 22-24.

Pevar, p. 22-24.

Pevar, p. 19-20.

Pevar, p. 2.

Pevar, p. 2.

Pevar, p. 2.

Pevar, p. 2.

Pevar, p. 9-10.

Nicholas Zaferatos, Planning the American Indian Reservation. (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. 2015), Kindle, p. 22-24.

Zaferatos, p. 23.

Pevar, p. 9-10.

Zaferatos, p. 25.

Pevar, p. 10-11.

Zaferatos, 25.

Pevar, p. 33.

Pevar, p. 33-34.

Pevar, p. 33-34.

Pevar, p. 34-36.

Pevar, p. 34-38.

Pevar, p. 34-38.

Zaferatos, p. 48-50.

Zaferatos, p. 48-50.

Zaferatos, p. 52-57.

Zaferatos, p. 52-57.

Zaferatos, p. 52-57.

Zaferatos, p. 36-38.

Amy Beth Hanson, “Montana Lawmaker Wants to Revisit Idea of Reservations,” AP News, (Helena), January 7, 2023, apnews.com/article/politics-new-mexico-state-government-montana-18a03c0ddfd91164d80d9b67390a8cce.

Ivana Saric, “White House will host first Tribal Nations summit since 2016,” Axios, November 14, 2021, https://www.axios.com/2021/11/14/white-house-tribal-nations-summit.