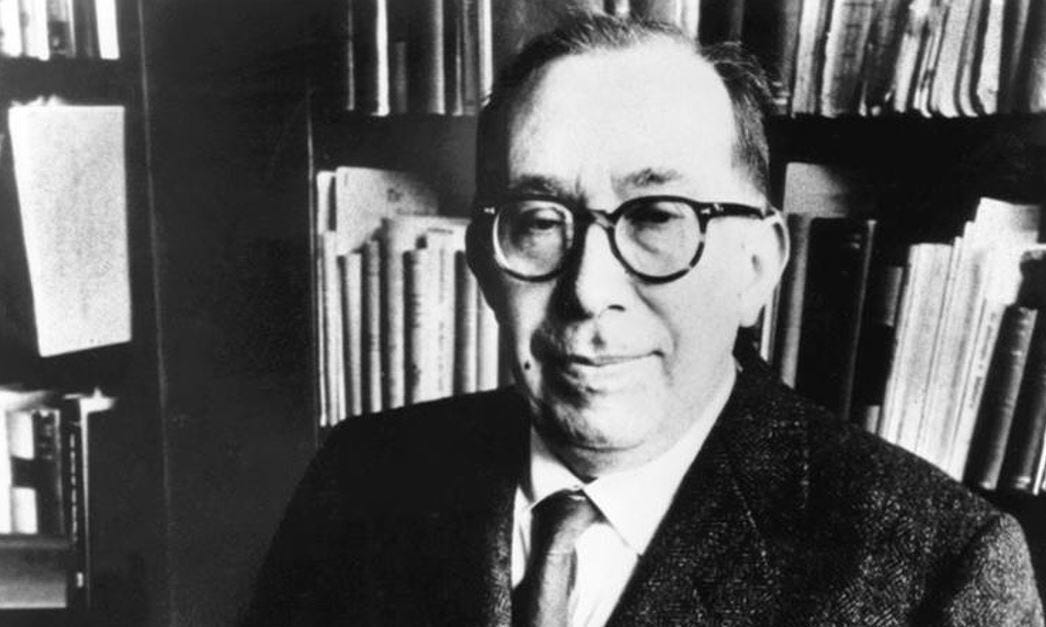

Widely considered as being one of the intellectual architects of neoconservative ideology—Leo Strauss was surely not a fan of communism and has left future generations of thinkers with a variety of ways to critique his life’s work. Nevertheless, in the context of political philosophy Strauss should still be recognized as an intellectual heavyweight in his own right and truth seekers should be open to using his work as an example to demonstrate that one can learn a great deal from intelligent people who they tend to disagree with—which also serves as a reminder of how critically important it is for societies to tolerate diversity of thought. As a committed scholar Strauss himself stated that he believed in this principle as well, remarking in his famous 1941 lecture titled German Nihilism that “Let us beware of a sense of solidarity which is not limited by discretion. And let us not forget that the highest duty of the scholar, truthfulness or justice, acknowledges no limits”1. Perhaps if there were more people who were committed to this objective and dispassionate take on humanity’s search for truth, the task of discerning justice in the complicated world of modernity would not be so heavily relegated to a minority of thinkers—for there can be no justice without truth. Not a relative truth as is celebrated in some circles today who like to believe in an ever elusive my truth—but instead the truth—regardless of what we would like it to be. Thus, in the spirit of this commitment to the intellectual honesty that is necessary for deriving meaning from the world we will be taking the time to reflect on Strauss’ German Nihilism because it provides careful readers of today with a rich yet sobering account of the intellectual environment that contributed to the rise of Nazi ideology in Germany following World War I.

Describing the contrast between the meaning of nihilism itself and the “German nihilism” which his thesis draws upon to explain the appeal that Nazism once had among some Germans, Strauss said that:

The fact of the matter is that German nihilism is not absolute nihilism, desire for the destruction of everything including oneself, but a desire for the destruction of something specific:* of modern civilization. That, if I may say so, limited nihilism becomes an almost* absolute nihilism only for this reason: because the negation of modern civilization, the No, is not guided, or accompanied, by any clear positive conception2.

This disdain of and desire for the destruction of modernity according to Strauss was a moral protest by German nihilists that was grounded in an objection to the definition of virtue that characterizes modern forms of morality that aspire “…to relieve man’s estate; or: to safeguard the rights of man; or the greatest possible happiness for the greatest possible number”3. In other words, the German nihilists who would eventually come to embrace Nazism during the reign of Germany’s Weimar Republic did so because they were opposed to a morality that aims to relieve suffering and protect the weak. Further elaborating on their central moral argument, Strauss said that this moral protest waged by German nihilists

…proceeds from the conviction that the internationalism inherent in modern civilization, or, more precisely, that the establishment of a perfectly open society which is as it were the goal of modern civilization, and therefore all aspirations directed toward that goal, are irreconcilable with the basic demands of moral life. That protest proceeds from the conviction that the root of all moral life is essentially and therefore eternally the closed society; from the conviction that the open society is bound to be, if not immoral, at least amoral: the meeting ground of seekers of pleasure, of gain, of irresponsible power, indeed of any kind of irresponsibility and lack of seriousness. Moral life, it is asserted, means serious life. Seriousness, and the ceremonial of seriousness—the flag and the oath to the flag—, are the distinctive features of the closed society… Only a life which is based on constant awareness of the sacrifices* to which it owes its existence, and of the necessity, the duty of sacrifice of life and all worldly goods, is truly human: the sublime is unknown to the open society4.

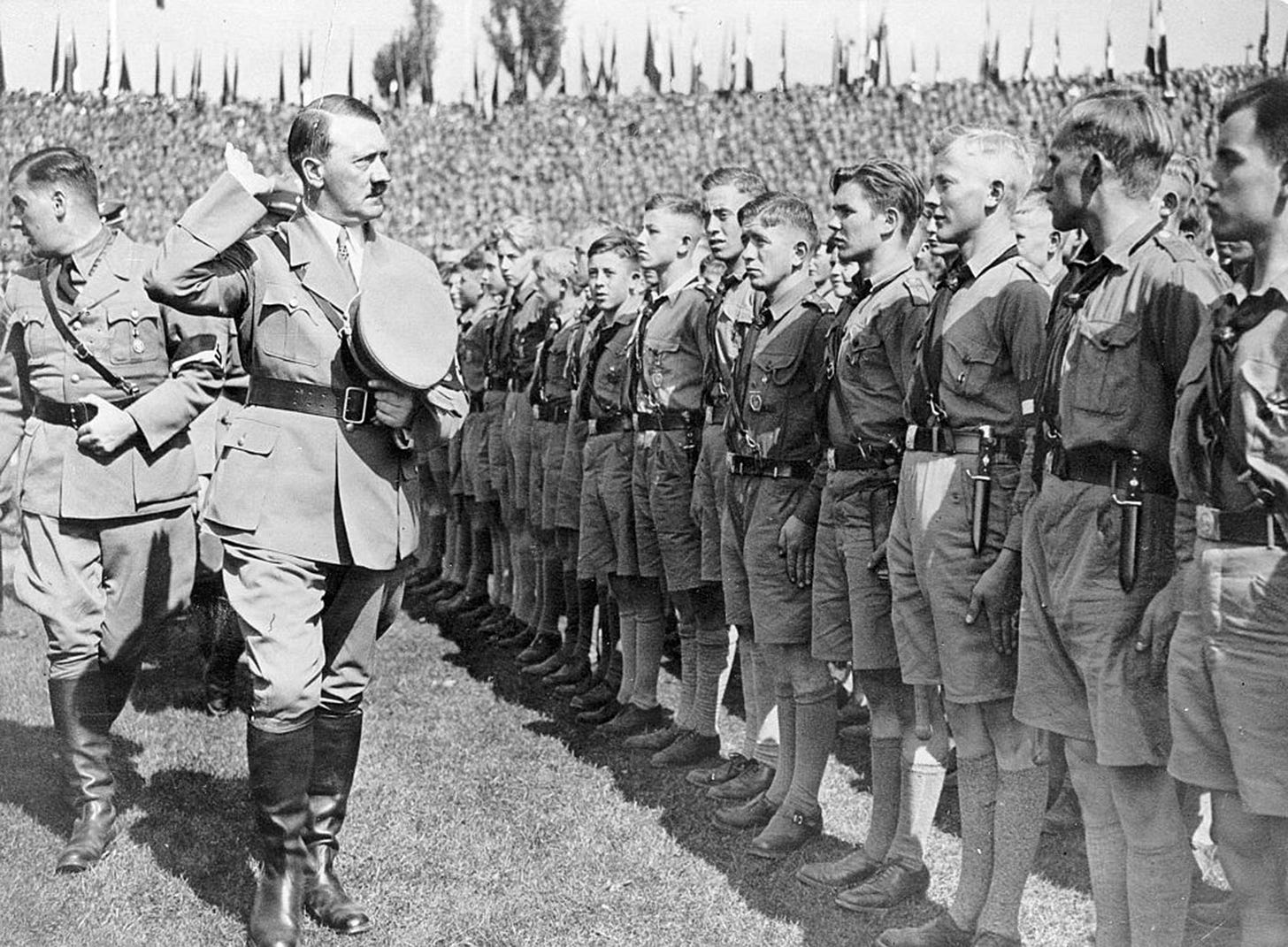

This underlying perspective which Strauss attributed to those who would become key supporters of Adolf Hitler’s regime deserves to be taken into consideration by those who wish to understand how a significant portion of a country could be persuaded into embracing a reactionary ideology like Nazism. The German nihilist critique of modernity’s morality is unique in that it isn’t suggesting that Hitler’s supporters were driven to embrace Nazism because they believed that doing so was in their economic interest. While perhaps a tempting answer for explaining their motivations given the infamous hyperinflation that preceded the Nazi’s rise to power, Strauss begged to differ with that explanation. On the contrary, he notes that those who became supporters of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP)—a political party which came to represent Germany’s militant, right-wing, and anti-Marxist brand of fascism—were highly concentrated in a portion of Germany’s youth population who he says were not “… worrying about their own economic and social position; for certainly in that respect they had no longer anything to lose…”5. Instead, he said that these young, atheistic, nihilists who would later become Nazis came to embrace their style of fascism in reaction to communism:

What they hated, was the very prospect of a world in which everyone would be happy and satisfied… a world without real, unmetaphoric, sacrifice… What to the communists appeared to be the fulfilment of the dream of mankind, appeared to those young Germans as the greatest debasement of humanity, as the coming of the end of humanity… they were unable to express in a tolerably clear language, what they desired to put in the place of the present world… the only thing of which they were absolutely certain was that the present world and all the potentialities of the present world as such, must be destroyed in order to prevent the otherwise necessary coming of the communist final order: literally anything, the nothing* the chaos, the jungle, the Wild West, the Hobbesian state of nature, seemed to them infinitely better than the communist-anarchist-pacifist future. Their Yes was inarticulate—they were unable to say more than: No! This No proved however sufficient as the preface to action, to the action of destruction6.

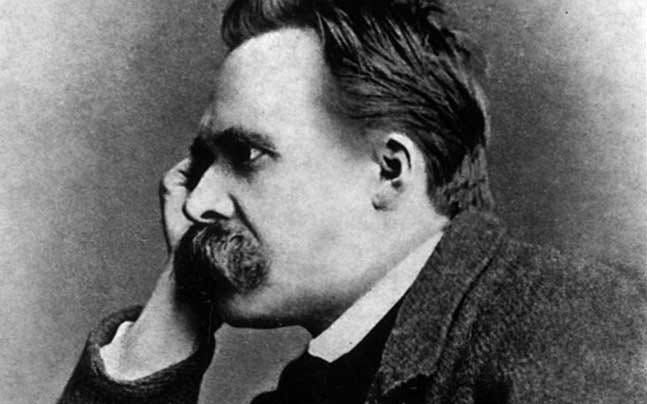

Strauss also suggested that nihilist philosophers like Friedrich Nietzsche bear some responsibility for the development of Nazism—as the ideology itself passionately espouses an atheistic worldview paralleling Nietzsche’s in the context of detesting equality and protecting the weak as moral virtues:

Nietzsche asserted that the atheist assumption is not only reconcilable with, but indispensable for, a radical anti-democratic, anti-socialist, and anti-pacifist policy: according to him, even the communist creed is only a secularized form of theism, of the belief in providence. There is no other philosopher whose influence on postwar German thought is comparable to that of Nietzsche, of the atheist Nietzsche7.

Support for this claim made by Strauss about the influence of Nietzsche’s atheistic inegalitarianism on the Nazi mental archetype can be drawn from observing Nietzsche’s own original writing. For example, in a passage addressing other intellectuals with similar views to himself, in his book Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future he singles out the ethical ideas promoted by the Christianity, Marxian socialism, and democracy as negative trends that his intellectual movement was at odds with, saying on his faction’s behalf that:

We have a different faith; to us the democratic movement is not only a form of the decay of political organization but a form of decay, namely the diminution of man… anyone who fathoms the calamity of lies concealed in the absurd guilelessness and blind confidence of “modern ideas” and even more in the whole Christian-European morality—suffers from an anxiety beyond comparisons… The over-all degeneration of man down to what today appears to the socialist dolts and flatheads as their “man of the future”—as their ideal—this degeneration of man into the perfect herd animal… this animalization of man into the dwarf animal of equal rights and claims, is possible…8.

Nietzsche’s writing style can be ambiguous in the sense that it doesn’t always convey his thoughts in a way that draws a direct contrast between his discussion of philosophy versus his discussion of politics. That being said, there are instances in his writing where he does express a message that is more overtly political than his more abstract philosophical ideas. Augmenting his negative evaluation of Western society’s movement towards democracy, in Beyond Good and Evil he forwards an argument in favor of establishing a specific kind of aristocracy—one that is explicitly guided by a creed radically distinct from “modern morality” but also from that which an aristocrat of the past might claim to be guided by:

The essential characteristic of a good and healthy aristocracy, however, is that it experiences itself not as a function… but as their meaning and highest justification—that it therefore accepts with a good conscience the sacrifice of untold human beings who, for its sake, must be reduced and lowered to incomplete human beings, to slaves, to instruments. Their fundamental faith simply has to be that society must not exist for society’s sake but only as the foundation and scaffolding on which a choice type of being is able to raise itself to its higher task and to a higher state of being…9.

Given the often-esoteric nature of Nietzsche’s rhetoric, noting the political prescriptions that he suggested more explicitly is thus significant to understanding what he saw as an acceptable vision for human society. In light of his loathing of democratic values and the intrinsically inegalitarian character of the aristocracy that he espoused support for, the “philosophy of the future” which he pointed towards can be described as such: a world of masters and slaves. A world in which nothing stands in the way of the strong oppressing the weak—who in his nihilistic view deserve to be oppressed by the strong who alternatively are to be exalted and even celebrated for exercising their will over others. From this perspective, man as we know him must transcend into a form of being that rejects the morality of the past along with anything else that can stop him from exercising his will—the only valid system of belief worthy of a true aristocrat in the Nietzschean sense of the term. Alluding to the overlap between the nihilistic creed held by Nietzsche and that of the Nazi’s, Strauss elaborated that:

There is reason for believing that the business of destroying, and killing, and torturing is a source of an almost disinterested pleasure to the Nazis as such, that they derive a genuine pleasure from the aspect of the strong and ruthless who subjugate, exploit, and torture the weak and helpless… German nihilism rejects then the principles of civilization… German nihilism on the other hand asserts that the military virtues, and in particular courage as the ability to bear any physical pain, the virtue of the red Indian, is the only virtue left… the implication is that we live in an age of decline, of the decline of the West, in an age of civilization as distinguished from, and opposed to culture… In that condition of debasement, only the most elementary virtue, the first virtue, that virtue with which man and human society stands and falls, is capable to grow. Or, to express the same view somewhat differently: in an age of utter corruption, the only remedy possible is to destroy the edifice of corruption—"das System"…10.

The Nazi’s strange belief that they could warp reality for the purpose of destroying the moral status quo of modern civilization; a status quo which they saw as the root source of a degenerate withering away of humanity by virtue of modernity’s tendency to seek the alleviation of suffering—is reflected in the writings of their Führer himself. In the chapter titled “Nation and Race” from Hitler’s autobiographical manifesto—Mein Kampf—the rhetorical parallel between his ideology and Nietzche’s is evident:

Those who want to live, let them fight, and those who do not want to fight in this world of eternal struggle do not deserve to live… international Marxism itself is only the transference, by the Jew, Karl Marx, of a philosophical conception, which had actually long been in existence, into the form of a definite political creed… Marx was only the one among millions who, with the sure eye of the prophet, recognized in the morass of a slowly decomposing world the most essential poisons, extracted them, and, like a wizard, prepared them into a concentrated solution for the swifter annihilation of the independent existence of free nations of this earth. And all this in the service of his race… Marxism itself systematically plans to hand the world over to the Jews… In opposition to this, the folkish philosophy finds the importance of mankind in its basic racial elements… it by no means believes in an equality of races, but along with their differences it recognizes their higher or lesser value and feels itself obligated, through this knowledge, to promote the victory of the better and stronger, and demand the subordination of the inferior and weaker… it serves the basic aristocratic idea of Nature and believes in the validity of this law down to the last individual…11.

While Hitler and other fascist ideologues of his time may have arguably not been consistently rational thinkers, Hitler’s expressed belief in a conspiracy theory linking the rise of communism with a plot to “hand the world over to the Jews” is worth noting when accounting for how the Nazis viewed the doctrines that they associated with the “open society”. Communism as explained by Strauss was hated by the Nazis because it is diametrically opposed to Hiter’s national socialism, for the socialism associated with Karl Marx’s communist ideology supports the belief that those who are weak should be protected from the strong and aims to relieve humanity’s suffering. Further, the reason that German fascists saw those goals as problematic was because they thought that without the experience of suffering humanity could never be truly moral and could never become elevated to a “higher state of being” as described by Nietzsche—a concept which Hitler’s Nazis would articulate as a movement towards becoming a new “master race”. Hitler’s fixation on Marx’s Jewish heritage is also worth noting as it demonstrates how his anticommunist rhetoric depicted communism as a foreign and therefore alien idea coming from outside rather than from within the “closed society” that his movement purported to protect and was instead a byproduct from the “open society” of the “modern civilization” that the Nazis so despised. Therefore, coming from the racist and eugenics-infused fascism that embodies Nazi thinking, the aim of communists to actively help the weak and reduce humanity’s suffering is not only heretical in a moral sense but also a recipe to weaken humanity and facilitate the withering away of human existence itself.

Being that the Third Reich and the broader German nihilist movement that preceded them were convinced that any kind of communist takeover would guarantee the rise of degeneracy naturally followed by the “greatest debasement of humanity”—this dimension of their thoughts, motives, and overall view of human nature shows that there could never be peace between fascists and communists. The connection between the thought patterns of Nietzsche and Hitler are strikingly noticeable when one recalls that they both expressed a shared the belief that the stronger are entitled to oppress the weaker and that the trend of growing democratization in Western countries represented a degenerate and therefore negative historical development. Both of them interestingly described their ideological aspirations as aristocratic as well. Moreover, one might even go as far as saying that Nietzsche’s publicized critiques of communism and what may be called “open society” movements became the intellectual prototype for the passionate anticommunism found in Nazi rhetoric—even if one concedes that he wasn’t the only thinker to inspire them. Strauss seemed to agree with this sentiment.

Referencing the failure of an out of touch academic establishment that did not understand the ideas and aspirations of their students well enough to have stopped them from becoming Nazis, Strauss said that among their flaws was their inability to recognize that “… one cannot refute what one has not thoroughly understood”12. Hence, the nihilist to Nazi pipeline flourished because it was not understood well enough by those who worked in the “open society” establishment institutions—which Strauss suggests was due at least in part to many adherents of the “open society” holding their ideas about modern civilization as a prejudice13. In turn, this prejudicial attitude prevented them from refuting Nazi propaganda and defending the value of modernity in a convincing way to those who favored the “closed society”14. Even the term “Nazi” is indicative of the mental bankruptcy that plagued progressive German intellectuals. The term itself was not what supporters of NSDAP called themselves—instead it was a derogatory term used by adherents of the “open society” aimed at Catholics in pre-Hitler Germany and later the NSDAP when they came to prominence in politics15. The original meaning of the word “Nazi” before the NSDAP came to power was in English the equivalent to a pejorative akin to “hillbilly”—which also explains why the NSDAP banned the usage of the word “Nazi” after they took power16. The prejudiced, dismissive, and even classist mentality of the Weimar Republic’s liberal progressives can be derived just by analyzing the way that they chose to repurpose that word. Their bourgeois political faction casted themselves as the culturally “superior,” “liberal,” or “progressive” people while they broadly wrote off their opponents as the people that they call “hillbillies”.

One may make a strong case that a broad dismissiveness was an appropriate attitude to take toward the political right in the lead up to the Nazi’s ascension to power. Yet when exploring the mentality of “progressives” in the context of the intellectual environment that the Nazi’s were emerging from, there was more than just a dismissive sentiment being conveyed in the original invocation of “Nazi”. A prejudiced sentiment helped inspire its use because it was being used to stereotype and direct condescension at a broader group of people than just the NSDAP—as was reflected by the German left’s choice to refer to members of the NSDAP with the same term that they used for the “hillbillies”. The message being communicated in the term was “People in Hitler’s party are like the hillbillies that we think are trash”. The typical Nazi may have not been able to articulate his thoughts very well, but neither could many of his opponents. Fast-forwarding to 2024, thoughtful observers of the Western world may notice that this sort of stereotyping behavior being described is eerily similar to the way liberal progressives living amongst bourgeois-cosmopolitan cultures use terms like “white trash” or maybe “deplorable” to describe any fellow citizen on the political right when they are in comfortable settings.

Recognizing the parallels between how liberal progressives in both pre-Hitler Germany and modern America have chosen to dismissively insult what are supposedly monolithic “right-wing” segments of their societies with hypocritically bigoted stereotypes is not an ideological concession to regressive political movements. Of course, the shift in use and meaning of “Nazi” from a slang pejorative to a word that identifies a specific political persuasion has long been completed and it is the duty of free humanity to identify Nazism when it emerges and eradicate it from the world anytime it gains a significant following. The term however should be reserved specifically for literal fascist scum rather than just being a loosely defined smear used to cynically discredit political rivals. Strauss’ account of what went wrong in the intellectual environment that facilitated Nazim’s rise provides a sobering warning of the potential consequences of doing otherwise. Promoting bad faith stereotypes about moderate political conservatives actually sends a message that encourages the right-wing and others to embrace Nazism because by associating them with fascistic movements any potential for common ground is willfully forgone and as a consequence this creates social space for fascists to court the support from everyone who the “progressives” decide to “cancel”. While this isn’t mentioned to suggest that Hitler’s rise was a product of a right-wing workers movement per se, it is also hard to believe that there were not valuable working class “hillbillies” in Germany who the left failed to unite with because they essentially told them that “You're not one of us, you're with the Nazis”.

For those of us finding that the social dynamics in pre-Hitler Germany as described by Strauss hit close to home, let us commit to not doing the fascist’s recruitment work for them. If we do not build the bridges necessary along class lines to unite the proletariat against the imperial capitalists quick enough, we risk losing the support of potential comrades to fascists who they would not support otherwise had their country’s respective communist party been there for them. In opposition to the swastika, the hammer and sickle on communist insignia represents proletarian solidarity between both the rural agricultural and urban industrial workers—a principled aspiration that would do us well to remember and get back to.

Leo Strauss, “German Nihilism,” Interpretation Journal – A Journal of Political Philosophy, vol. 26, no. 3, (1999): p. 363.

Strauss, 357.

Strauss, 358.

Strauss, 358.

Strauss, 360.

Strauss, 360.

Strauss, 361-362.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future (New York: Vintage Books Random House Division, 1989), 117-118.

Nietzsche, 202.

Strauss, 369-370.

Adolf Hitler, “Nation and Race,” ed. Terrance Ball and Richard Dagger, Ideals and Ideologies: A Reader (New York: Pearson Longman, 2011), 313, 323-324.

Strauss, 362.

Strauss, 362.

Strauss, 362.

Nirmal Dass, “The Strange Origin of the Word ‘Nazi’,” Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture, January 2022, https://chroniclesmagazine.org/society-culture/the-strange-origin-of-the-word-nazi/.

Dass, “The Strange Origin”.

Share this post